There used to be a question asked of trainee teachers: why do we teach Shakespeare and not Pinball?

It’s the sort of question that got a certain sort of politician angrily demanding that the lefties be kicked out from the teacher training colleges. The question annoyed me too when I first heard it (although when I was asked the question they said video games, not pinball).

But when I began to think about it, I realised that it was an excellent question. Possibly the most important question in education. It wasn’t so much about Shakespeare v Pinball, but rather about the value we place on different skills and knowledge. Why do we have the curriculum that we have?

The realistic answer, of course, is to make people employable.

One hundred years ago we taught people to add up columns of numbers. We were preparing clerks to work with ledgers. Nowadays students are taught how to use calculators or spreadsheets to solve problems. Different jobs, different education.

When I was at school the girls learned cooking and sewing, the boys woodwork and metalwork. Later on, girls could opt for what was called office skills: how to take shorthand and use a typewriter. My wife, studying 200 miles away in Wales, bucked the trend by taking A level physics and chemistry.

To put this in context, I was 9 when the Equal Pay Act came into force, meaning that women were paid the same as men for the same work. 15 years later, when I started teaching, it was taken for granted that girls and boys studied the same subjects.

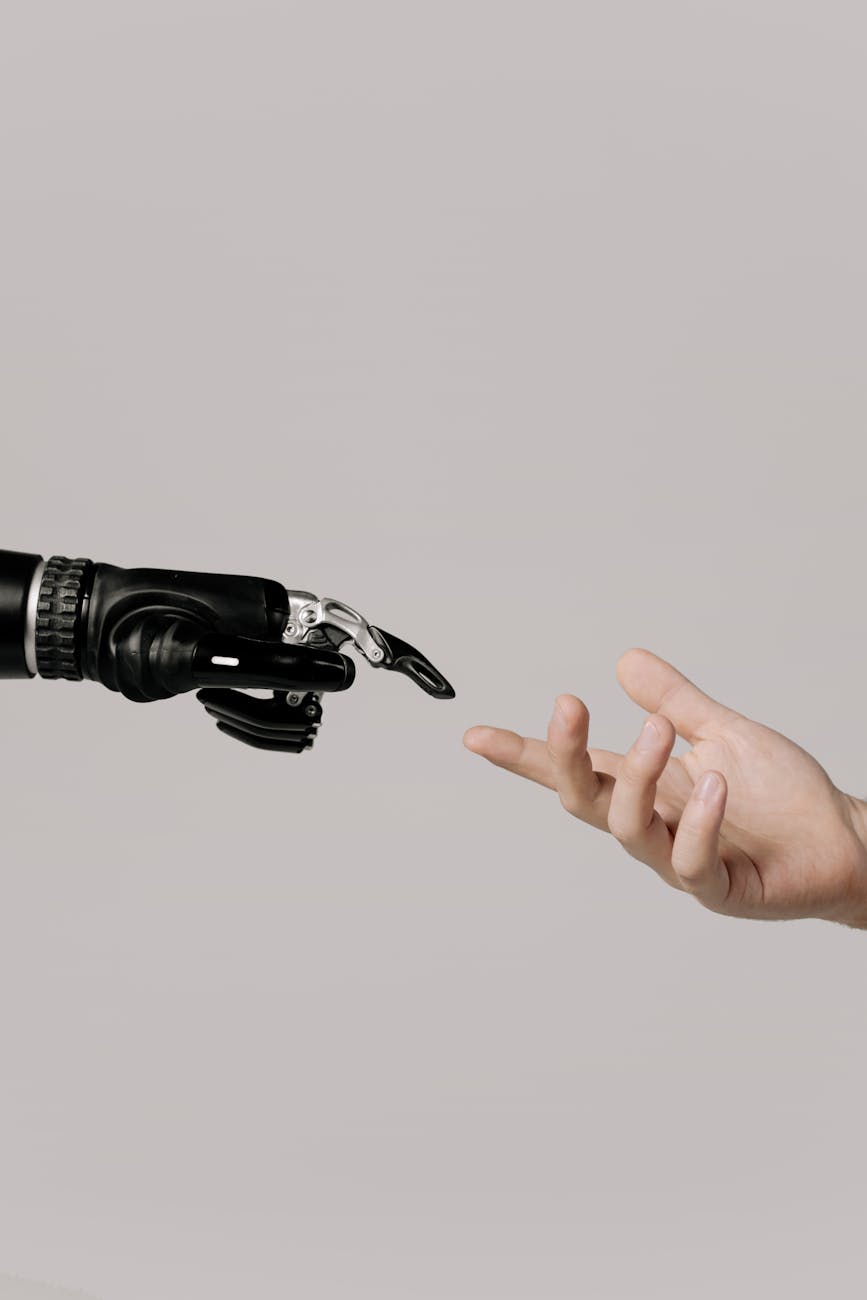

When I started reading SF, just about the time of the Equal Pay act, I was led to believe that machines would do all the jobs in the future. SF promised humans a life of leisure. That prediction seems to have been half right. Nowadays, it seems, machines are indeed doing more and more jobs, but we humans seem to be working longer hours for less reward.

Which brings me to the news of the UK government’s curriculum review, announced yesterday.

The media made much of the fact that students would learn more about AI in the future. That makes sense.

But there was one rather heartening announcement that wasn’t really mentioned in the news reports: that changes to league tables will mean arts GCSEs “will be given equal status to humanities and languages, recognising their value in boosting confidence and broadening skills for a competitive job market.“

Note that phrase, competitive job market. Like I said, education is all about making people employable.

But who cares? The arts have been slowly ground out of state schools over the past ten years. I think it’s a good thing that students will have the chance to start writing, painting and composing again. If the AIs are going to be doing all the jobs in the future, then at least students will have something interesting to fill their lives.

Maybe we can start to realise the second half of that 1970s vision of SF. Because I’m not sure it’s going to be that pleasant a future if we don’t…