As I mention last week, I’ve moved my notes to Obsidian. I’m going to talk about Obsidian another time, for the moment I want to talk about the notes themselves. Specifically, why I’ve converted all my notes to markdown.

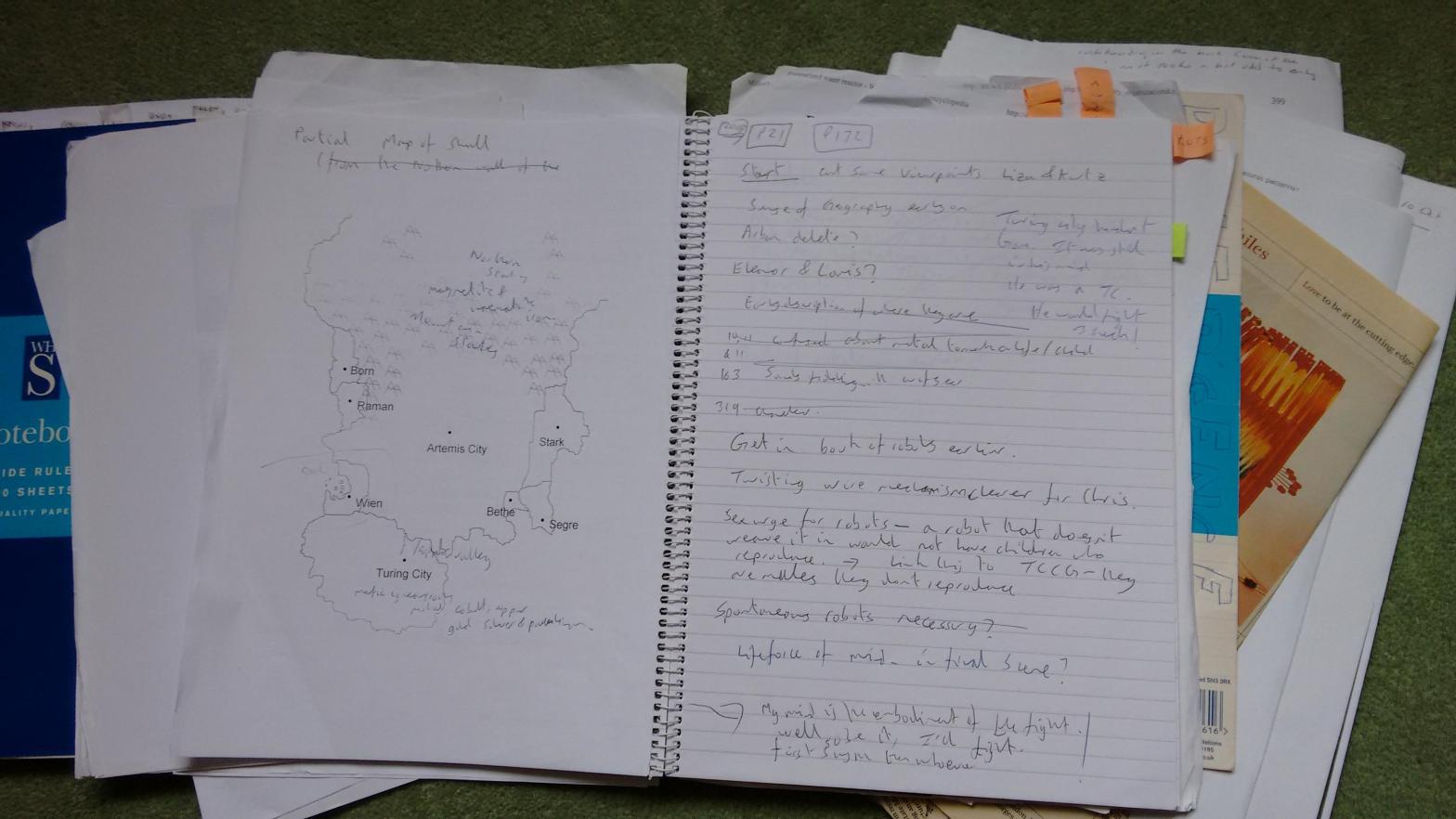

A writer lives by their notes. Ideas; scenes; character sketches; dialogue; impressions, all carefully recorded and waiting to take on life someday in a story. I remember seeing Poul Anderson’s carefully typed list of story ideas in the science fiction museum in Seattle and feeling a warm glow of recognition. Not only that, but validation. I was doing this right.

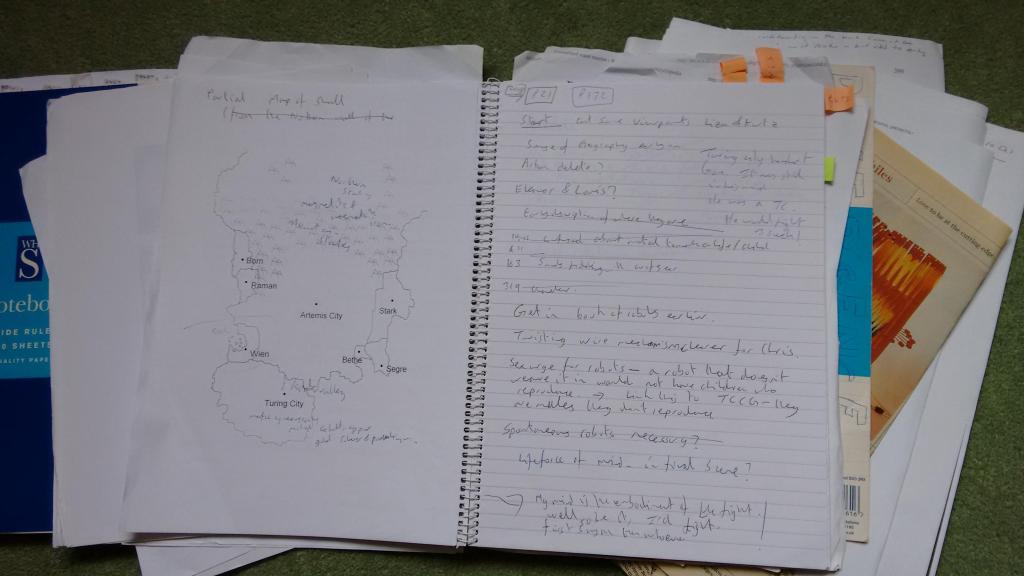

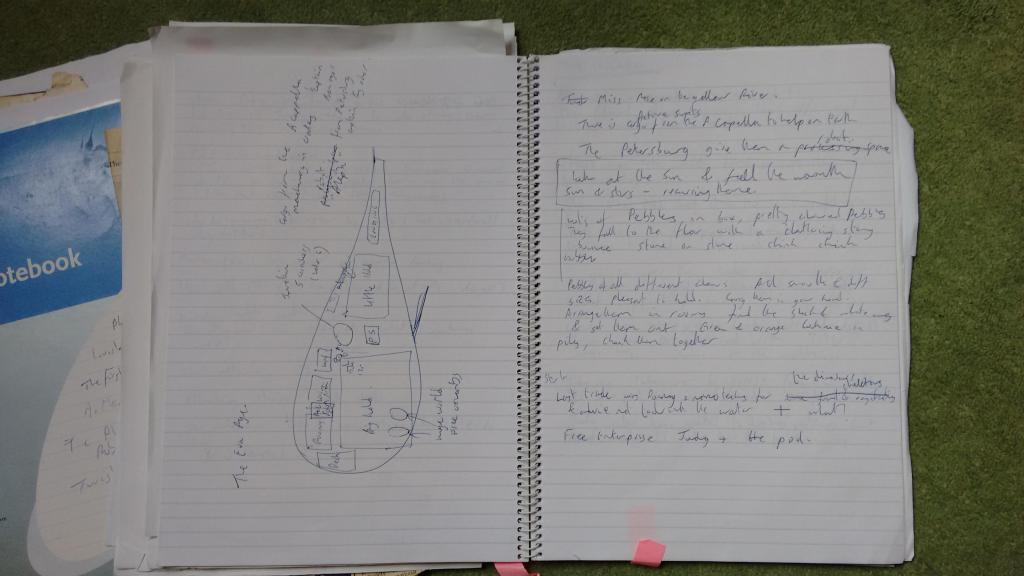

I’ve got notes going back decades. Notes written in old exercise books, cheap reporter’s notebooks and expensive leather bound journals. I’ve experimented with devices such as Psion Organisers, Palm Pilots and even an iPod Touch.

The trouble with storing notes electronically used to be exporting them to a new device. Cross platform software like Evernote was a revelation as it meant you only needed to enter your notes once and then you could find them anywhere.

Evernote, Apple Notes, One Note and the like are fantastic. But what if you want to change to a new application? That’s where the problems arise.

The trouble is the way your notes look on the screen is not the same as the way your notes are stored on the computer.

Take this example

Here’s how Evernote stores the above

<note>

<title>This is a Heading</title>

<created>20230727T080748Z</created>

<updated>20230727T080830Z</updated>

<note-attributes>

<author>Tony Ballantyne</author>

</note-attributes>

<content>

<![CDATA[<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="no"?>

<!DOCTYPE en-note SYSTEM "http://xml.evernote.com/pub/enml2.dtd"><en-note><ul><li><div><span style="color:rgb(0, 0, 0);">Here’s some text</span></div></li><li><div><a href="https://tonyballantyne.com" rev="en_rl_none"><span style="color:rgb(0, 0, 0);">Here’s a link to my website</span></a></div></li></ul><div><span style="color:rgb(0, 0, 0);"><span style="--en-markholder:true;"><br/></span></span></div></en-note> ]]>

</content>

</note>

If you look carefully you can see the original text, along with metadata such as when the note was created, and formatting data such as the text colours. It’s hard to extract the relevant information from all that.

It’s worth noting, by the way, that Evernote is one of the good guys, they make it easy to export your data, they don’t go out of their way to obfuscate things and keep you in their system.

Here’s a better way of storing the above, this time using markdown.

# This is a Heading

- Here's some text

- [Here's a link to my website](https://tonyballantyne.com)

Looking at that you can understand why it would be sensible to store your notes in that format. It’s easy to read, it’s easy to transfer.

That’s why I’ve converted all my notes to markdown. They’re now stored on my devices, not in the cloud. I can invest the time in getting them just right without having to worry about having to convert them in the future.

So what about Obsidian? Obsidian has many fantastic features that I’ll talk about later, but the bottom line is that it functions as a markdown reader and editor.

In other words, if I decide I don’t like Obsidian in the future, I’ll simply choose another application that handles markdown.

Here’s what Stephan Ango, one of the guys behind Obsidian, has to say about this.